Initial Research into Organizational Democracy

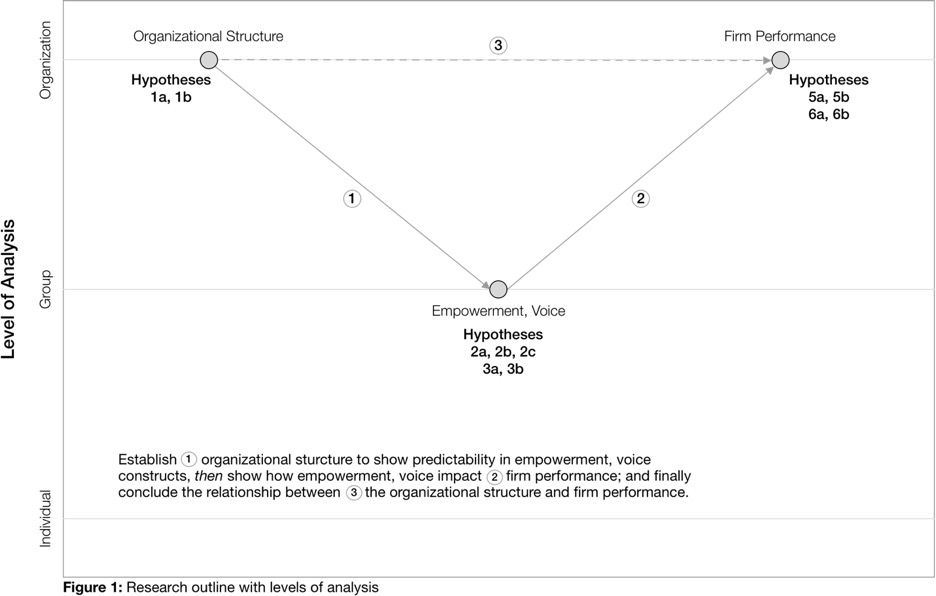

This paper reviews existing literature on organizational theory and design, specifically organizational democracy, to develop an emergent theory showing how firms who adopt structurally anchored organizational design are more likely to empower employees, leading to improved overall firm performance.

Proposed Research on the Effects of Organizational Democracy on Work Group and Firm Performance

Abstract

This paper reviews existing literature on organizational theory and design, specifically organizational democracy, to develop an emergent theory showing how firms who adopt structurally anchored organizational design are more likely to empower employees, leading to improved overall firm performance. First, the current context is explored from both political and strategic management perspectives. Second, existing meanings and requirements of organizational democracy are reconciled into a single working definition. Third, the relationships between the structural form, empowerment, and firm performance are explored. Finally, an empirical methodology is outlined to demonstrate the connection between organizational democracy and improved firm performance. I elaborate on the meaning of organizational democracy and the degree to which organizations benefit adopting its principles. The contemporary context of business and society focusing on the growing trend towards inequality (particularly in the U.S.) creates an appropriate backdrop for a return to more egalitarian ideals. The assumption that organizational democracy is best suited to handle the multi-objective organization underpins the paper and is the basis for the proposed hypotheses.

My sincerest gratitude to Professor Travis Grosser who introduced me to the concept of holocracy, invested his time to support me through a thoughtfully crafted independent study plan, and ushered me into the world of academic research.

Introduction

As the purpose of firms shifts away from maximizing shareholder profit (Friedman, M., 1970) towards a more holistic stakeholders’ perspective (Business Roundtable, 2019), corporations need to understand how structure impacts their organizational performance within these new guidelines. This evolution from shareholder value to stakeholder values represents a shift not merely in attitude but in how we incorporate a variety of perspectives and balance competing interests (e.g., firm financial objectives collide with community objectives). Previous efforts to reconcile diverging interests (e.g., a moral imperative) include conscious capitalism, which aims to incorporate major stakeholders (e.g., customers, employees, investors, communities, suppliers, and the environment) to better adhere to changing marketplace expectations. Such efforts deny the need for structural change, instead opting for pledges in behavior and shifts in strategy, marketing, and communications. To understand the significance, consider two perspectives from (1) political science and (2) strategic management.

A political perspective

It is easily forgotten that the purpose of the firm was not always to “maximize shareholder profit”; our imaginations struggle to see what else is possible. However, some have turned to shining light on the structural inconsistencies in our society and its economy. In an article regarding a future beyond hierarchy, Laloux (2015) directly points to the irony, that “we scoff at the idea that you could run an economy through central planning, and yet, we still unquestionably accept that that is the best way to run an organization.” How then, can we personally value a free society, equality, and liberty and then somehow put our individual values aside when we go to work? How did we get to this point?

The establishment of the free-market — culminating in the work of Adam Smith — was to fulfill an egalitarian goal of equality, to disrupt the monarchy and the monopolies it bestowed upon the few — not merely to create economic growth. In this way, being egalitarian is to “commend and promote a society in which its members interact as equals” (Anderson, 2017). Anderson argues all of this was derailed by “social hierarchy” and the Industrial Revolution. One aspect of this is the effects of Taylorism and scientific management. As engineers broke down processes and tasks into their smallest components, required skills were ultimately stripped away where possible — enabling owners to hire workers at a much lower wage. Perrow (1986) remarks that we are only now “beginning to painfully rediscover and recommend giving back to the workers a small part of what had been their own property, in the form of such schemes as job enlargement, workers’ participation, workers’ autonomy, and group incentives.”

To consider this perspective is to reflect on the relationship between business and society, and the role of equality as a force for change. The very inequalities that existed in the western world in the seventeenth century appear to be making a modern comeback (Anderson, 2017).

A strategic management perspective

There does exist another perspective, one that may speak more directly to our 21st century corporate sensibilities. This represents a shift in structurally how we are setup, and suggests we are ill-prepared. Not only is this underpinning of corporations changing — assuming corporate leaders are to be taken seriously — the continual increase in task uncertainty (Galbraith, 1973) and complexity along with technological change has also pushed us to consider new forms of organizing (Galbraith, 1973; Siggelkow and Rivkin, 2005). Consider the firm that declares this new multi-stakeholder reality:

- If multiple-stakeholder organizations create a dynamic complexity; and

- Hierarchies are ill-suited for dynamic complexities (Galbraith, 1973; Gresov, 1989; Volberda, 1996);

- Therefore, multi-stakeholder organizations with structural hierarchies need alternative structures (i.e., non- or less-hierarchical structures) to best fulfill their purpose

As task uncertainty increases, less structure is advantageous — as the effect of uncertainty is to “limit the ability of the organization to preplan or make decisions about activities in advance of their execution” (Galbraith, 1973). As uncertainty increases work is less predictable and therefore more exceptions are expected. In such situations, the options become either to address the frequency of handling exceptions (i.e., reduce frequency) or relax the structure to accommodate more exceptions (i.e., increase capacity). The latter suggest improving lower-level decision-making capabilities. As opposed to some management practices where the goal is to minimize variation (e.g., scientific management), another viewpoint emerges whereas variation is not to be changed but is accounted for and handled appropriately. Organizations’ strategies are explicitly linked to their structures and relate to task uncertainty. Complex, non-routine tasks that require more creativity and innovation, are especially present in today’s knowledge-based economy.

While there is evidence that hierarchies are less adept when it comes to uncertainty, the possible complexities caused by competing values in a multi-stakeholder organization are not fully appreciated (Ashforth and Reingen, 2014; Battilana, et al., 2017).

Hypothesis 1a: Multiple-stakeholder organizations create a dynamic complexity

Hypothesis 1b: The more non-hierarchical an organization is, the more its values align with multiple stakeholders

If assumptions in hypothesis 1 proves to be correct, public discourse and research in strategy are both pointing to a need for structural change. As it turns out, there is a new form of organizing called organizational democracy — which is, in fact, not new but rather new in that limited attention has been paid to it.

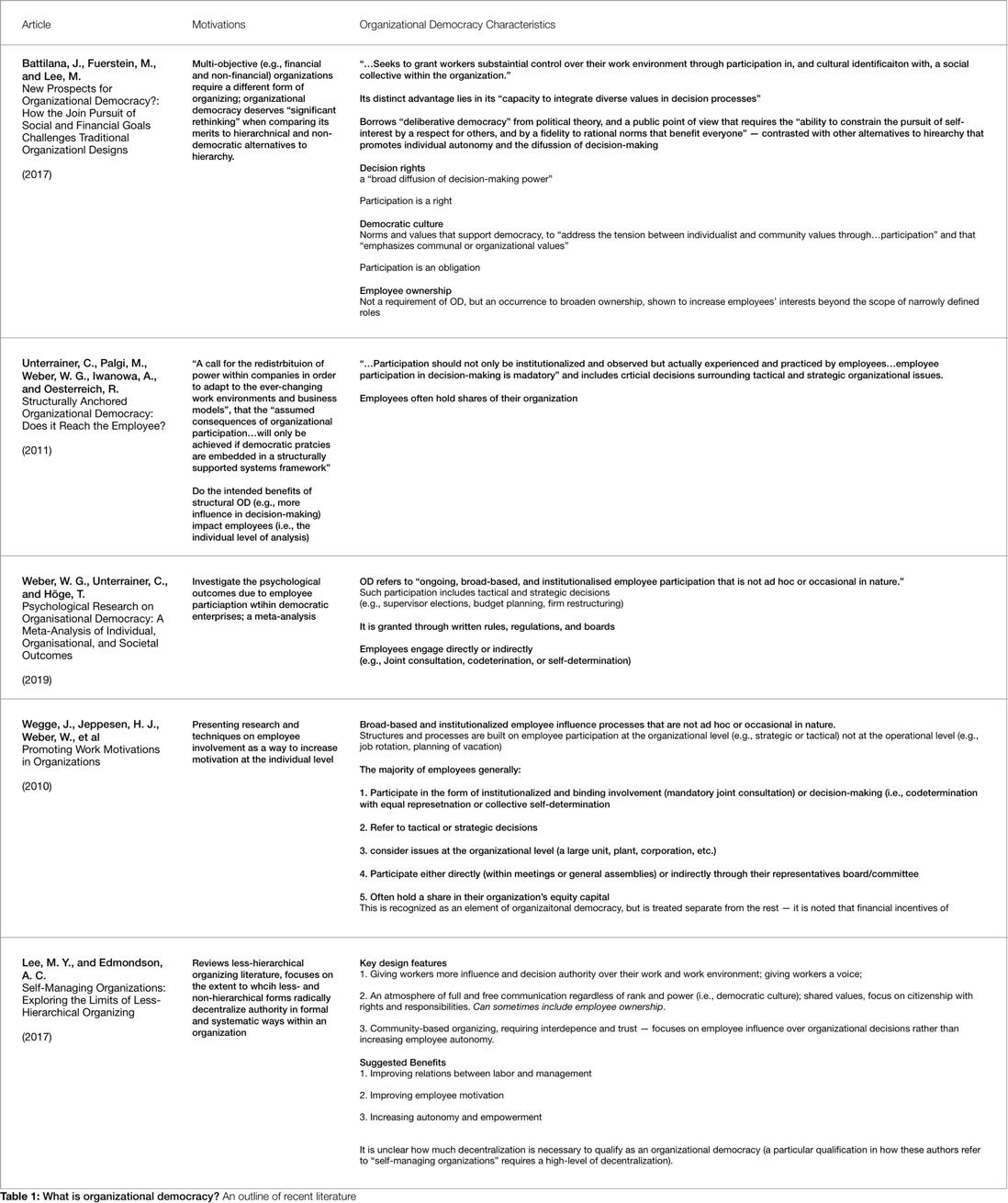

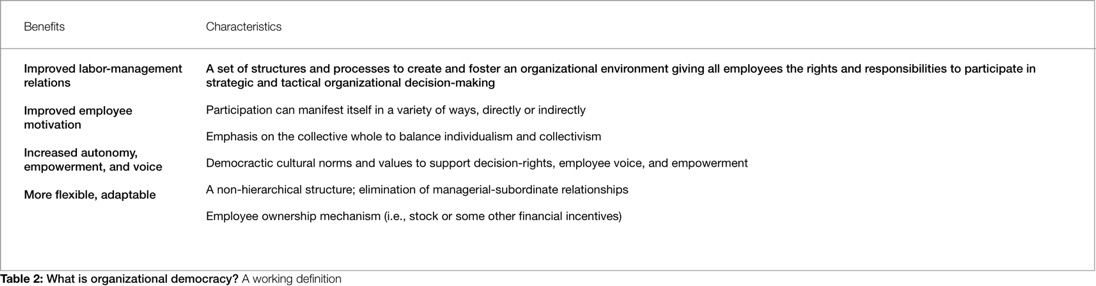

A Return to Organizational Democracy

Organizational democracy [1] (OD) is a set of structures and processes used to create an organizational environment giving all employees the rights and responsibilities to participate in strategic and tactical decision-making (Wegge, et al., 2010; Battilana, et al., 2017; Lee & Edmondson, 2017). [2] A defining characteristic is the emphasis on the collective whole (Battilana, et al., 2017; Lee & Edmondson, 2017) which builds the “capacity to integrate diverse values in decision processes” (Battilana, et al., 2017) at the organizational level (Wegge, et al., 2010) to reconciling individualism and collectivism. In this way, participation is an obligation and regularly on-going. The ways in which employees participate can vary (e.g., directly or indirectly, Wegge, et al., 2010; Weber, Unterrainer & Höge, 2019). Additionally, to support institutional participation and decision rights, a culture that values democratic principles is necessary (Battilana, et al., 2017) to instill an “atmosphere of full and free communication” (Lee

& Edmondson, 2017). One aspect overlooked in much of the literature is the manager-subordinate relationship (i.e., managerial hierarchy, Lee and Edmondson, 2017), evoking a

quote attributed to the late Steve Jobs: "It doesn't make sense to hire smart people and tell them what to do; we hire smart people so they can tell us what to do." In addition to the aforementioned characteristics defining OD, I argue the elimination of managerial hierarchy is tantamount to a democratic culture in supporting structural employee participation. Furthermore, the “structurally anchored” OD designation (Unterrainer, et al., 2011) is avoidable because in the context of this paper OD is by definition structural. Table 2 has an outline of the defining benefits and characteristics of OD.

There is a lack of consensus amongst researchers as to the degree to which an organization needs to adhere to these structures and processes to be considered an OD. To add to possible confusion, employee ownership (e.g., equity shares) is a common aspect accompanying OD, but is not considered a requirement. Sauser (2009) emphasizes the importance of employee ownership specifically when it takes place alongside employee participation in decision-making. It is this concept of decision-making that is perhaps the most important aspect of OD. Decisions are choices in resource allocation. If we then see power as being an “asymmetric control over valued resources” (Magee & Galinsky, 2008) then we can understand the connection between — and therefore the significance of — decision-making in the context of organizational structure and employee empowerment. Because of this, empowerment and voice are important constructs we will consider further.

Empowerment

Empowerment is perhaps inherent to the goals of OD given its close association with employee participation (Gilson, Mathieu, & Maynard, 2012). The construct of empowerment is known to promote employee performance and can be broken down into two components: structural empowerment and psychological empowerment. Gilson, et al. discuss structural empowerment as the “transition of authority and responsibility from upper management to employees” and cites Kanter in stating:

“structural empowerment is primarily concerned with organizational conditions (e.g., facets of the job, team designs, or organizational arrangements that instill situations, policies, and procedures), whereby power, decision making, and formal control over resources are shared.” (emphasis added)

Since structural empowerment has been established to be antecedent to psychological empowerment, there can be little doubt it must be inextricably linked with OD. Yet there is much to uncover about both the antecedents and outcomes as a result of empowerment (Gilson et al., 2012). As OD introduces an appreciation for the collective, the focus of our understanding of empowerment transitions from the individual to work groups (i.e., teams).

Hypothesis 2a: The more organizational democracy is present in an organization, the stronger its employees’ structural empowerment.

Hypothesis 2b: The more organizational democracy is present in an organization, the stronger its employees’ psychological empowerment, such that the relationship between structural empowerment and psychological empowerment will correlate with the degree which OD is adopted by the organization.

We also see where “humanistic management” (Lee and Edmondson, 2017) describes efforts to “soften its edges” where the managerial hierarchy is concerned and falls short of driving structural change. This creates a say-do gap, whereby organizations espousing certain values are not always bound to practice said values.

Hypothesis 2c: Organizations that maintain a managerial hierarchy are less likely to exhibit structural empowerment, regardless of the degree to which all other organizational democracy is present.

Voice

If we assume a level of optimism in that most employees will maintain engagement with the organizational democracy through participation mechanisms, we are then concerned with participation behaviors. Not all participation is created equal. Whereas in traditional hierarchies individuals’ contributions (e.g., perspectives, values, opinions, thoughts) are governed by their supervisors, OD gives space for employee voice to exist. Voice is the expression of challenging but constructive, opinions, concerns, or ideas about work-related issues by employees with the intent to make improvements (Morrison, 2011). According to LePine and Van Dyne (1998), researchers haven’t found a reliable way of predicting voice — and less research has concerned the antecedents of voice. Research in voice has focused on either person-centric or situation-centric variables. Neither of which has taken into consideration the affect structure has, and the extent to which structure can help predict voice. OD, by definition, implicates empowerment, but a missing nuance from this is voice. Voice speaks to a special kind of participation that has shown promise in that it is linked to organizational effectiveness. Voice also links an organizational structure to values held by employees (LePine & Van Dyne, 1998). Voice is inherently risky for employees as it requires “practice and assertive nonconformance”. By baking in employee participation, we expect a culture in which such risky behavior is deemed less so, and therefore more employees would feel inclined to engage. Self-managed groups — marked by more involvement and responsibility (e.g., decision-making ability) — exhibit more voice. Because of this, it is expected that teams in OD structured firms will exhibit more voice.

Hypothesis 3a: The more organizational democracy is present in an organization, the stronger its work groups exhibit voice.

Hypothesis 3b: Work groups with more voice reflect a wider spectrum of values, more representative of the organization at-large.

Structure and Firm Performance

By observing two key variables within organizational democracy — empowerment and voice — and in order to contribute to existing literature, the relationships between these factors and firm performance should be understood. Firm performance, for the purpose of this paper, refers to financial performance and employee satisfaction metrics. How employees are managed does influence performance (Gittell, et al., 2010) and team effectiveness and its effect on performance has been neglected (Gilson, et al., 2015).

Hypothesis 5a: Work groups with more empowerment, both structural and psychological, will have stronger, positive firm performance.

Hypothesis 5b: Work groups with more voice will have stronger, positive firm performance.

At the heart of hierarchy is decision-making. It is shown that the centralizing properties of hierarchy are linked to improved firm performance and the quickness that information flows within an organization. While this may be the case, I argue that such hierarchy is less capable when it comes to considering multiple stakeholder values — values which contribute a diversity of perspectives — and has a greater impact on overall firm performance.

Hypothesis 6a: The degree to which organizations embrace multiple stakeholder values positively relates to an increase in firm performance.

Hypothesis 6b: There is a positive relationship between the presence of organizational democracy and firm performance, which is mediated by multiple stakeholder values.

Experimental Design

Current events and changes in the U.S. business environment have sponsored a renewed interest in research into alternative organizational forms, yet many unanswered questions and untested assumptions remain. This research proposal is for an empirical study where data collection will largely consist of surveys and interviews.

To measure the degree to which any organization adheres to OD, criteria similar to those developed and used to survey and classify OD in organizations (Weber, et al., 2008; Unterrainer, et al., 2011) is the template to follow. This tool would be very useful, especially in hypotheses 1b, 2x and 3x.

When considering the group-level in hypotheses 2x and 3x, analysis needs to include both compilation and composition models. By considering both models, weighted attributes can be considered as well as the particular combinations, while minding the aggregate effects at the group-level.

Discussion

There are concerns surrounding organizational democracy, particularly (1) limited evidence to demonstrate or prove out its benefits, and (2) that it lacks certain practicalities; these two categorical concerns are interconnected. Suggested benefits of OD are improving labor relations with management, improving employee motivation, and increasing autonomy and empowerment (Lee & Edmondson, 2017). Beyond questions of whether or not promised benefits can be actualized, concerns are largely born out of the application of political theory to business context, especially in how accountability will translate in the work environment (Kerr, 2004), evidence that suggests that employees will choose not to participate (Kerr, 2004; Harrison, et al., 2004) skepticism about the boundaries in which it can exist (Bacharach, 1989), such as whether it can scale (Battilana, et al., 2017) appropriately. The dominant viewpoint that hierarchy outperforms non-hierarchical systems (Battilana, et al., 2017) only helps to reinforce the status quo (Magee & Galinsky, 2008) and the predominately hierarchical way of organizational life is a significant hurdle to the adoption of significant structural change.

While there may be evidence that organizational democracy has benefits over more traditional forms of organizing, several questions remain, particularly:

- What are the boundaries on organizational democracy theory?

- Does the benefit of implementing OD outweigh the costs of transitioning existing firms?

In OD, where there is a balance between individualism and collectivism, how is autonomy handled? Further exploration into research on autonomy could help explain this relationship between individual and collective rights.

A potential hypothesis to explore surrounds employee ownership: the more an organization is aligned with OD, the presence of employee ownership in a firm will partially mediate employee participation. This is an interesting question, but for the purpose of this paper seemed to deviate from the central narrative.

Whereas organizational democracy borrows its ideology from the political realm, the actual theories need to be developed. There is much not known or confirmed about the behaviors and outcomes of OD. A weakness of this area of research is the number of firms to empirically study. The compromise here is to measure the degree to which a firm adheres to the strict definition of the OD structure. The key distinction through much of this is structural versus psychological, that is have we simply attempted to make employees feel a certain condition is true or have we gone so far as to make it structurally true. To feel as though you have power, when in fact the old power structure remains intact.

When considering the empirical study, I gave thought to how data collection would happen and continue to be concerned about the quality of the data. Would I be able to find and document enough organizations across the spectrum (especially those who actually practice OD) to make real, persuasive conclusions? Do we know enough about such theory to do more empirical studies? Should we instead pursue an ethnographic study much like the one Ashforth, B. E., & Reingen, (2014) conducted. What assumptions are necessary for organizational democracy to come about? An ethnographic study within firms that practice OD might enhance our understanding and uncover new hypotheses worth testing — or to challenge our understanding of the contexts (i.e., boundaries) in which OD can take hold.

Finally, of the literature reviewed, there was a considerable lack of acknowledgement in the U.S.-based publications for the European-based journals. Whether this is due to a lack of clout or quality, or simply geographic differences

Conclusion

In the last decade, the business environment has been largely affected by societal inequities and many prominent firms are signaling a change to a multi-stakeholder purpose. Organizational democracy has some compelling properties to help address the inclusion of various values and perspectives in the workplace, yet inclinations towards hierarchy and the maintaining of existing power structures is a formidable force for the status quo. In another way, many of the employees who would be potential beneficiaries of such a structure as OD are also skeptical since hierarchy is in a sense ingrained in how we all think and operate.

For those interested in improving labor-management relations and who consider the strategic management perspective on firm performance, this area of research offers considerable opportunity to discover a better way of organizing to align to the environment and achieve more flexible coordination internally.

REFERENCES

Anderson, E. (2017). Private Government: How Employers Rule Our Lives (and Why We Don’t Talk about It). Princeton University Press.

Ashforth, B. E., & Reingen, P. H. (2014). Functions of Dysfunction: Managing the Dynamics of an Organizational Duality in a Natural Food Cooperative. Administrative Science Quarterly. 59 (3) 474-516.

Bacharach, S. B. (1989). Organizational Theories: Some Criteria for Evaluation. The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct., 1989), pp. 496-515.

Battilana, J., Fuerstein, M., & Lee, M. (2017). New Prospects for Organizational Democracy?: How the Joint Pursuit of Social and Financial Goals Challenges Traditional Organizational Designs. In R. Subramanian (Ed.), Capitalism Beyond Mutuality, Oxford University Press. Forthcoming.

Business Roundtable (2019). Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘An Economy That Serves All Americans’. https://opportunity.businessroundtable.org/ourcommitment. August 19, 2019.

Conscious Capitalism (2013). Conscious Capitalism Credo. https://www.consciouscapitalism.org/credo.

Friedman, M. (1970). The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. The New York Times Magazine. http://umich.edu/~thecore/doc/Friedman.pdf?mod=article_inline. September 13, 1970.

Galbraith, J.R. (1974). Organization design:An information processing view. Interfaces,4: 28-3.

Gilson, L. L., Mathieu, J. E., & Maynard, M. T. (2012). Empowerment—Fad or Fab? A Multilevel Review of the Past Two Decades of Research. Journal of Management, Vol. 38 No. 4, July 2012 1231-1281.

Gilson, L. L., Lim, H. S., Litchfield, R. C., & Gilson, P. W. (2015). Creativity in Teams: A Key Building Block for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. The Oxford Handbook of Creativity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship, Chapter 11. Oxford University Press.

Gittell, J. H., Seidner, R., Wimbush, J. (2010). A Relational Model of How High-Performance Work Systems Work. Organization Science, Vol. 21, No. 2 (March-April 2010), pp 490-506.

Gresov, C. (1989). Exploring fit and misfit with multiple contingencies. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34: 431-453.

Harrison, J. S., & Freeman, R. E. (2004). Special Topic: Democracy In and Around Organizations: Is organizational democracy worth the effort? Academy of Management Executive, 2004. Vol, 18, No. 3.

Lee, M. Y., & Edmondson, A. C. (2017). Self-managing organizations: Exploring the limits of less-hierarchical organizing. Research in Organizational Behavior, 3, 35-58.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (1998) Predicting Voice Behvior in Work Groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol 83. No. 6, 853-868.

Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). Social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status. Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 351-398.

Morrison, E. W. (2011) Employee Voice Behavior: Integration and Directions for Future Research. Academy of Management Annals. Vol 5, No. 1, June 2011, 373-412.

Perrow, C. (1986). Complex organizations: A critical essay. NY: McGraw-Hill.

Sauser, W. I. Jr. (2009). Sustaining Employee Owned Companies: Seven Recommendations. Journal of Business Ethics, 84:151-164.

Siggelkow, N., & Rivkin, J. W. (2005), Speed and Search: Designing Organizations for Turbulence and Complexity. Organization Science, 16: 101-122.

Unterrainer, C., Palgi, M., Weber, W.G., Iwanowa, A., & Oesterreich, R. (2011). Structurally Anchored Organizational Democracy: Does it Reach the Employee? Journal of Personnel Psychology, 2011; Vol. 10(3):118-132.

Volberda, H. (1996). Toward the flexible form: How to remain vital in hypercompetitive environments. Organization Science, 7(4), 359374.

Weber, W. G., Unterrainer, C., & Höge, T. (2019). Psychological Research on Organisational Democracy: A Meta-Analysis of Individuals, Organisational, and Societal Outcomes. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 2019, 0(0), 1-63.

Wegge, J., Jeppesen, H. J., Weber, W. G., Pearce, C. L., Silva, S. A., Pundt, A., Jonsson, T., Wolf, S., Wassenaar, C. L., Unterrainer, C., & Piecha, A. (2010). Promoting Work Motivation in Organisations: Should Employee Involvement in Organisational Leadership Become a New Tool in the Organisational Psychologist’s Kit? Journal of Personnel Psychology; Vol. 9(4):154-171.

[1] Synonyms for organizational democracy include industrial democracy (Battilana, et al., 2017; Unterrain, et al. 2011) and workplace democracy (Lee & Edmondson, 2017)

[2] From a limited review of recent literature, the ways in which OD is described does vary. An overview of the literature and their motivations is presented in Table 1.