A critique on conscious capitalism

Conscious capitalism is said to be a framework for achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals, but in a more practical application for U.S. firms it is unclear how well suited it is to tackle the major concerns facing capitalism in the 21st century. There is a disconnect between the profit motive and who is served by it, that is to say there is disagreement whether we have a single stakeholder (i.e. shareholders) or multiple stakeholders (e.g., customers, investors, community). This paper aims to explore the topic of business purpose through the lens of conscious capitalism and agency theory and whether conscious capitalism is getting business to aspire to more.

Introduction

Last summer, Ezra Klein got exceptionally personal on his podcast, The Ezra Klein Show. In the episode he admits an unease taking about his veganism, but continues by queuing up the conversation by setting the stage — evoking images of the inhumane treatment of animals (emphasis mine):

There isn’t really disagreement over whether pigs, cows, and chickens feel pain. I don’t know people really who defend factory farming. There are laws in every state against cruelty towards animals. If there was a sick cow and you just saw me kicking it, you would stop me. You would be appalled. But these laws, these anti-cruelty laws they have this one giant loophole. You can pretty much be as cruel as you want to be to farm animals. You can do to a lamb things you would be jailed for doing to a cat. This is what makes the way we eat and the way we think about the way we eat so strange. You don’t need to accept any new ideas to be horrified, you just need to believe the ideas you already accept. You just need to see what you’ve been taught to stop seeing…You see people you love and admire participating in unbelievable cruelty all the time. You see a world where there is so much suffering being caused for so little reason that it’s breathtaking. I call it ‘taking the green pill’. All of a sudden, you do this one thing, you make this one change in you perception not even a big one, and a world that seemed completely normal becomes a horror show.

This conversation was memorable and parallels the sentiment that emerges when talking about the purpose of business and illustrates this dilemma I see within capitalism. The dilemma is the moment when the profit motive is at odds with the other proclaimed values. Can we say we support our community and look the other way when the very thing we do works against their best interests — in the same way we are disgusted by the idea of abusing dogs and cats, but happy to grab a rotisserie chicken from the deli?

Klein doesn’t simply say killing animals is immoral, rather he pokes at a discontinuity in our logic (e.g., eating cows: good, eating dog: bad) and in doing so begins to expose a disconnect in our values. Similarly, Conscious Capitalism exists to draw attention to the occasions when firms act at odds with public interest and showcase firms who adopt its approach. Where this falls short is in how far it goes to push for a structural shift in how business fundamentally behaves.

Capitalism, at least in the way it is practiced today, is under attack — especially by the millennial generation. I think there are a variety of issues in play and I want to focus on ownership and stakeholder issues. The purpose of this paper is to explore the intersection of purpose and agency theory through the context of conscious capitalism. While it is the intention to form a specific perspective and to articulate an opinion, it is the start of a longer conversation.

What is Conscious Capitalism?

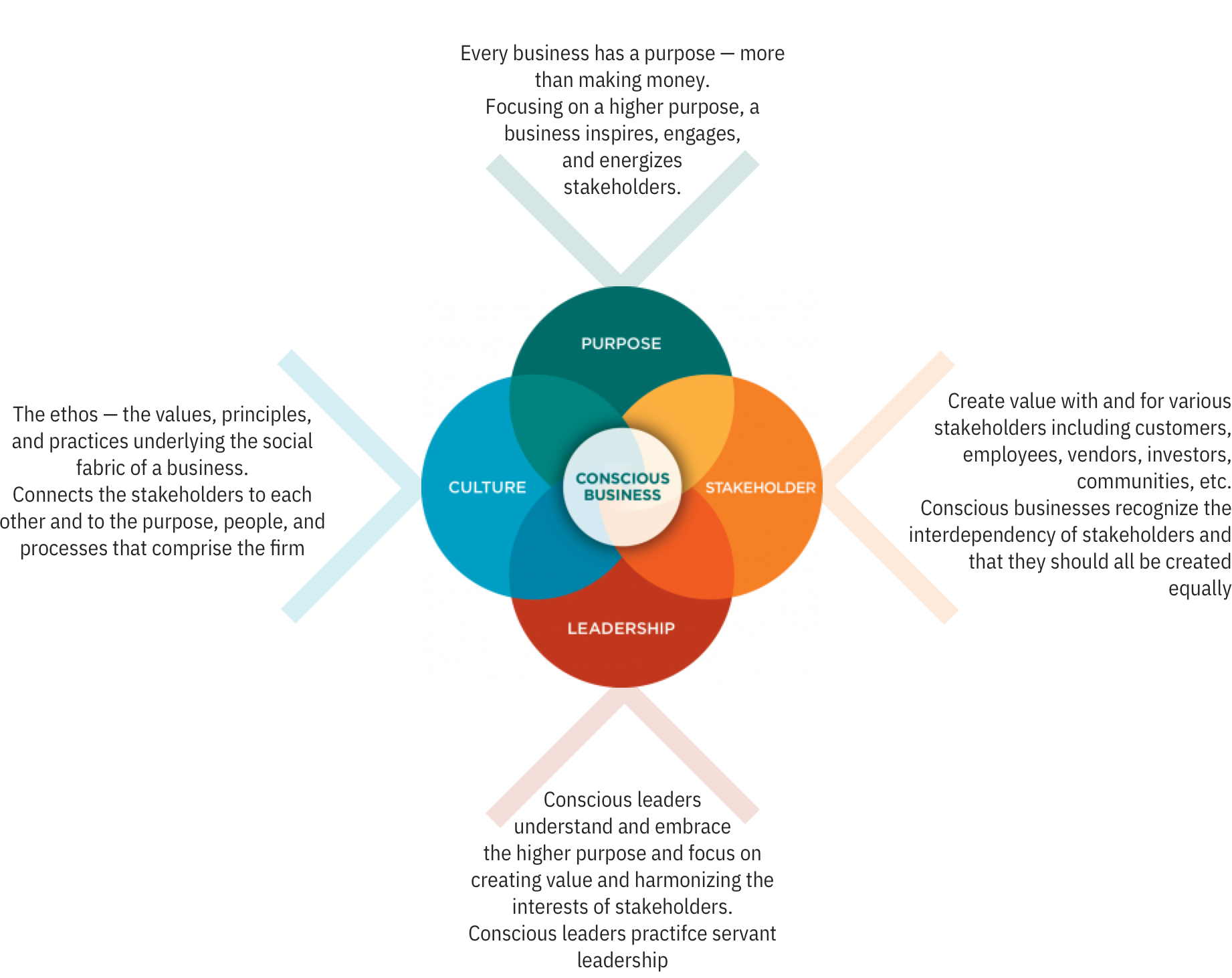

Conscious Capitalism is defined as “a philosophy based on a simple idea that when practiced consciously, business innately elevates humanity. This philosophy is rooted in a set of guiding principles: the four tenets of higher purpose, stakeholder orientation, conscious leadership, and conscious culture.” It is through the adoption of these tenets that firms can steer clear of such things as greed and misconduct. A consortium of businesses, it holds each other accountable to the alignment of purpose and profit for shared prosperity. Through a credo, they share how the four tenets interact to “[reflect] where we are in the human journey…and the innate potential of business to make a positive impact on the world.” It is through business and a faith in capitalism that will empower the global community to thrive. (See Figure 1 for a visualization and detail on each of the four tenets.)

It can be said that Conscious Capitalism does not ride in the face of the profit motive, but advances the conversation to answer the question “to whom does it profit”. Their answer to this question is all major stakeholders including customers, employees, investors, communities, suppliers, and the environment. (In fact this list has a lot in common with general business sustainability efforts, particularly customers, suppliers, and the environment.)

Conscious Capitalism allows business leaders to strike a balance between the four priorities and in doing so announce those guiding principles in a way those who have not pledged allegiance to its credo cannot. But there is another aspect to this worth highlighting.

Why the need for “Conscious” Capitalism?

The Conscious Capitalism organization provides this as their response to this very question.

Capitalism works. Period. Its power to positively change lives is unparalleled. But misuse of capitalism’s power by some has led to negative stereotypes such as greed, misconduct and exclusion. This inaccurate way of thinking about business seemed destined to be an unshakable narrative — until now. There is a better way to be a capitalist. A way that will create a better world for everyone. A way forward for humankind to liberate the heroic spirit of business and our collective entrepreneurial creativity so we can be free to solve the many challenges we face. Conscious Capitalism provides that path.

Where this response falls short is in addressing where business is actually failing — resulting in such stereotypes. Instead, this positions themselves as more a public relations play.

If we accept that Conscious Capitalism is in favor of capitalism and they are in favor of a profit motive — rather, they are for the expansion of the stakeholder definition beyond shareholders — then what they should be challenging is agency theory. The ideals set forth by conscious capitalism is safe from dispute, as far as this critique is concerned. However, the concern is it does not go far enough to make the structural changes necessary to actually advance capitalism in the 21st century.

A criticism of conscious capitalism

The first criticism of conscious capitalism comes from the idea that it is an effort that does not go far enough to make meaningful structural changes to a firm. In his presentation, Bingaman highlighted the four tenets, but failed to make any real distinction between what these tenets say and what is required by a firm that is a registered benefit corporation (aka B-corp). This would seem to be a natural next step, that conscious capitalism would lead to the logical conclusion that more firms should transition into B-corps. Interestingly, when I posed the question, Bingaman pointed out the issue of access to investment. He said investors are uninterested in B-corps because there is less room to make the returns they need. Understandable, but isn’t this the type of aspiration that conscious capitalism should be aiming for and the leadership it should be developing?

Turning away investors because of conscious business decisions can happen regardless of this decision to be a B-corp. This was the case with Juno, a ride-hailing app company where, “according to a person familiar with its operations, the founders sold the company and agreed to cut its driver stock awards because they couldn’t find new investors to finance its growth.” It would seem incongruence between conscious capitalism and investor priorities puts any firm at risk — so why become a conscious business?

The second criticism of conscious capitalism is that it may actually be a means to an end only. In a recent event with Alan Schnitzer, CEO of Travelers, he mentioned their laser focus on generating a high return to shareholders. “Before you gasp” he said, prefacing his words, knowing full well how this is not a popular stance. However, he argued that while this is their goal it cannot happen without giving credence to the needs of employees, customers, communities, etc. The implication of his message was of course business exists to maximize shareholder value and you would be a fool if you think you can do that and ignore your constituencies. Schnitzer concluded the remark by stating “If [managers] don't accomplish maximizing shareholder value, there will be someone else in [the CEO’s] chair telling you what you'll be doing next year.” Could it be the tenets of conscious capitalism have less to do with driving change in business and more to do with what is necessary to achieve success in this 21st century economy? Again, Bingaman shared a number of firms who practiced conscious capitalism and their ability to outperform in the market. It is conceivable this has more to do with firms doing good business whist doing good by their people. (At the time of writing this, Travelers was not listed within the credo or business partner sections of the Conscious Capitalism website.)

One final note from Bingamen, he refers to a quote from Anna Lappé that every dollar spent is a consumer casting a vote. Do we really? Yes, it would seem plausible that if a target market stopped patronizing your business, it would have a significant affect on your revenue. This kind of capitalistic activism expects consumers have acceptable alternatives and, ironically, demands a level of consciousness from consumers to be aware and moved to take collective action. Like an invited guest who won't RSVP until they know their friends have also committed, social change doesn't happen by relying on individual in silos. It might start there, but it must happen publicly in a coordinated effort. The idea is nice, but a little trite.

Agency theory

Having been born in the 1980s, it is hard to think there was a time when investors did not reign supreme. In fact, it was not until the 1970s when Harvard Business School professor Michael Jensen developed agency theory. From a Harvard Business Review (HBR) article:

Yet the idea that corporate managers should make maximizing shareholder value their goal—and that boards should ensure that they do—is relatively recent. It is rooted in what’s known as agency theory, which was put forth by academic economists in the 1970s. At the theory’s core is the assertion that shareholders own the corporation and, by virtue of their status as owners, have ultimate authority over its business and may legitimately demand that its activities be conducted in accordance with their wishes.

Conscious Capitalism appears to only concern itself with this theory — now heavily indoctrinated — at arms length. By not weakening or re-writing agency theory, it does not address the underpinning ideas driving the prime goal in today’s economy.

An interesting point when talking about agency theory is the specific call its authors make for firms not to fall victim to the concern of social responsibility. Considerations “they argue, mistakenly imply that a corporation is an ‘individual’ rather than merely a convenient legal construct.” How can we operate under such circumstances as agency theory? What else of what they wrote assumes corporations are not individuals and does this hold up in a post Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission world?

Lastly, it is worth making one more point, that business theory is based on small business and much of what has significantly affected society is due to the effects of large business. As revealed by David Souder, Interim Dean of the University of Connecticut School of Business, in a correspondence:

This is ‘big business’ – once you have a profit, you have an obligation to use those profits to try to earn more profits. And in the world where ‘all else equal’ holds, that is not only defensible but also, as [Adam Smith] argued, good for society. The problem is that there are some pretty obvious ways to use profits earned in the past to make things unequal (to your own benefit) in the future. And so, big business demands an economic theory designed for the reality that it’s pretty hard to find contemporary situations in advanced economies where all else is actually equal. Our theories are underdeveloped relative to our reality.

The same HBR article continues to outline five flaws within the agency theory model:

- Agency theory is at odds with corporate law: Legally, shareholders do not have the rights of “owners” of the corporation, and managers are not shareholders’ “agents.”

- The theory is out of step with ordinary usage: Shareholders are not owners of the corporation in any traditional sense of the term, nor do they have owners’ traditional incentives to exercise care in managing it.

- The theory is rife with moral hazard: Shareholders are not accountable as owners for the company’s activities, nor do they have the responsibilities that officers and directors do to protect the company’s interests.

- The theory’s doctrine of alignment spreads moral hazard throughout a company and narrows management’s field of vision.

- The theory’s assumption of shareholder uniformity is contrary to fact: Shareholders do not all have the same objectives and cannot be treated as a single “owner.”

The fourth point is particularly concerning, especially where conscious business overlaps with business sustainability efforts. The obsession of meeting stock analyst expectations (i.e., short-term) in the face of a long-term, sustainable horizon is exactly the kind of thing conscious business should be changing.

The assumptions made in our models and the theories developed are in need of repair. Some believe this “evolution” will come from conscious capitalism, but while the sentiment is there it is hard to see how until it directly confronts business-as-usual.

Conclusion

The critique of capitalism is en vogue, especially as it relates to inequality, and this is not an attempt to ride that train. It is the intention of this paper to offer a critique of conscious capitalism through the lens of business purpose and agency theory. By considering the concept that corporate managers aim to maximize shareholder value, as prescribed by agency theory, we should understand what this implies and how conscious capitalism addresses this. While it is not the sole tenet (as there are three others) the idea of purpose and who for whom the purpose serves is at the heart of what conscious capitalism wants to address.

If we consider the analogy of the moral imperative as viewed by the vegan, to end animal cruelty and by extension our use of meat in our diets, then we should acknowledge the logical discontinuity (e.g., eating cow: good, eating dog: bad) and see similarities in how we view shareholders as the sole stakeholder in the U.S. firm. It has not always been this way and it does not need to be, but we must learn to see what we already know to be.

If I may take the vegan analogy a step further, In the same podcast episode, Melanie Joy rebuts the notion that it is enough for an individual to merely reduce their intake of meat. Conscious Capitalism’s effort is equivalent to the sympathetic eater who acknowledges their situation, but whose response is only to reduce consumption not eradicate it.

In a similar vein, I wonder if publicly pledging to four tenets — by one account things necessary for any worthy business leader — does anything more than make a for a good PR story. The aim of conscious capitalism is about aspiring to be more through the practice of capitalism, to reflect our humanity. If it truly wants to do this, it should go beyond tenets and loosen the grip agency theory has on business.

Further critique of conscious capitalism and how it can improve capitalism and embrace our humanity should investigate:

- how else does agency theory has enabled today’s business culture

- looking for examples where such efforts failed (e.g., Juno)

- why have there not been more firms to join the effort?